The bulk of large plastic bits in the North Pacific garbage patch have been lost or discarded by fishing vessels.

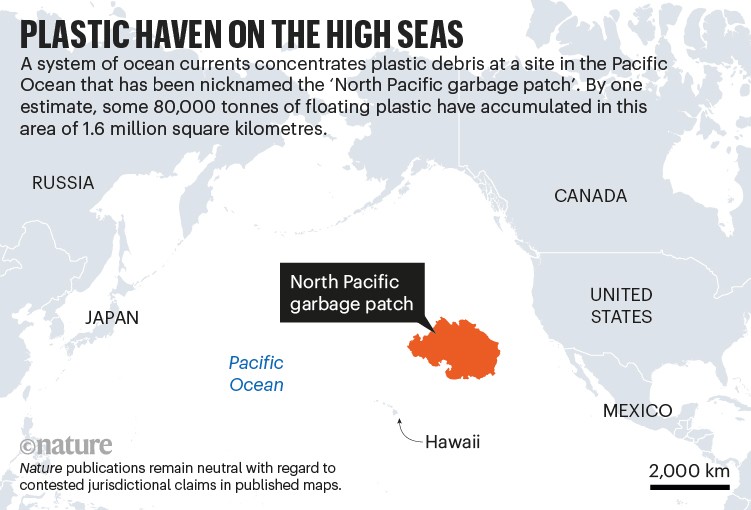

Fishing gear from just five regions could account for most of the floating plastic debris in the ‘North Pacific garbage patch’, a vast swathe of the North Pacific Ocean that holds tens of thousands of tonnes of plastic.

A study published on 1 September in Scientific Reports1 found that as much as 86% of the large pieces of floating plastic in the garbage patch are items that were abandoned, lost or discarded by fishing vessels. The finding is counterintuitive, given that most marine plastic makes its way into the ocean through rivers.

These findings “change our understanding of the sources of plastic in the North Pacific garbage patch”, says Matthias Egger, an ocean plastic researcher at the Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit organization based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, that develops techniques to remove plastic from the oceans. The information could help to shape future policy to reduce plastic pollution in the ocean, he says.

A sea of plastic

The contaminated area was discovered in 1997 when a ship’s crew, sailing from Hawaii to California, noticed plastic littering a remote stretch of the open ocean. The plastic accumulates where ocean currents converge, forming a ‘garbage patch’ that some researchers estimate includes 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic. This debris is sometimes mistaken for food by turtles and other animals, and can trap wildlife.

In 2018, a survey2 found that fishing nets made up nearly half of the debris. The nets clearly came from fishing vessels, but the research team couldn’t determine the source of the rest of the plastic in the area. So, in 2019, the Ocean Cleanup collected more than 6,000 floating items totalling around 547 kilograms from the patch, and analysed the debris for letters and logos to pin down its origins.

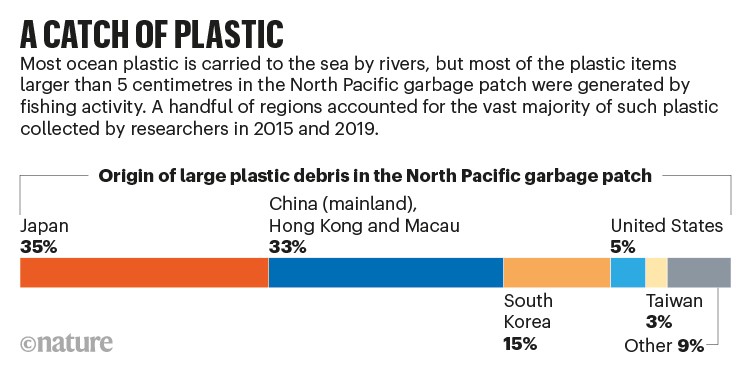

The researchers determined production dates for dozens of items, including a buoy dating back to 1966. They were also able to track down the regions of origin of 232 objects. One-third of the identified debris came from Japan — possibly in part because of the tsunami that hit the country in 2011 — with the rest split between Taiwan, the United States, South Korea and the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Macau.

Notably absent from the debris was plastic from nations with lots of plastic pollution in their rivers. This was surprising, says Egger, because rivers are thought to be the source of most ocean plastic. Instead, most of the garbage-patch plastic seemed to have been dumped into the ocean directly by passing ships.

This suggests that “plastic emitted from land tends to accumulate along coastal areas, while plastic lost at sea has a high chance of accumulating in ocean garbage patches”, Egger says. The combination of the new results and the finding that fishing nets make up a large proportion of the debris indicates that fishing — spearheaded by the five countries and territories identified in the study — is the main source of plastic in the North Pacific garbage patch.

Fishing for rubbish

“What this paper and other investigations have shown is that there is really one sector — fishing — responsible for this plastic,” says Lisa Erdle, director of science at the 5 Gyres Institute, an ocean-research organization in Los Angeles, California. Knowing how plastic ends up in various environments can help to inform policy choices and clean-up tactics, such as putting trackers on nets, she says.

This information could also be used to shape the United Nations Treaty on Plastic Pollution, which has been under negotiation since March 2022, says Egger. But more directly, “the findings highlight the vital role of the fishing and aquaculture industries in making ocean garbage patches a relic of the past”, he says.